NOTE: THIS DOCUMENT IS OBSOLETE, PLEASE CHECK THE NEW VERSION: "Mathematics of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), with Audio Applications --- Second Edition", by Julius O. Smith III, W3K Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9745607-4-8. - Copyright © 2017-09-28 by Julius O. Smith III - Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA), Stanford University

<< Previous page TOC INDEX Next page >>

Frequencies in the ''Cracks''

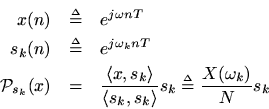

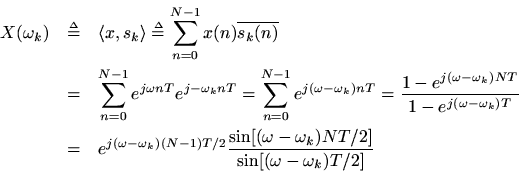

The DFT is defined only for frequencies

. If we are analyzing one or more periods of an exactly periodic signal, where the period is exactly

samples (or some integer divisor of

), then these really are the only frequencies present in the signal, and the spectrum is actually zero everywhere but at

. However, we use the DFT to analyze arbitrary signals from nature. What happens when afrequency

is present in a signal

that is not one of the DFT-sinusoid freqencies

?

To find out, let's project a length

segment of a sinusoid at an arbitrary freqency

onto the

th DFT sinusoid:

The coefficient of projection is proportional to

using the closed-form expression for a geometric series sum. As previously shown, the sum isat

and zero at

, for

. However, the sum is nonzero at all other frequencies.

Since we are only looking at

samples, any sinusoidal segment can be projected onto the

DFT sinusoids and be reconstructed exactly by a linear combination of them. Another way to say this is that the DFT sinusoids form a basis for

, so that any length

signal whatsoever can be expressed as linear combination of them. Therefore, when analyzing segments of recorded signals, we must interpret what we see accordingly.

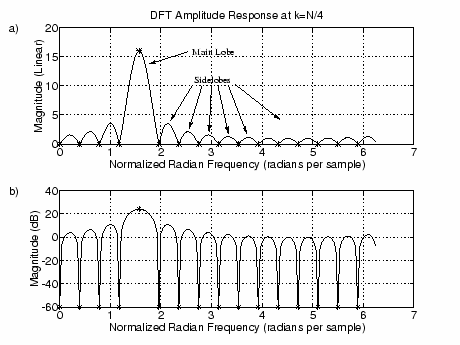

The typical way to think about this in practice is to consider the DFT operation as a digital filter.7.1 The frequency response of this filter is what we just computed,7.2 and its magnitude is

(shown in Fig. 7.3a for). At all other integer values of

, the response is the same but shifted (circularly) left or right so that the peak is centered on

. The secondary peaks away from

are called sidelobes of the DFT response, while the main peak may be called the main lobe of the response. Since we are normally most interested in spectra from an audio perspective, the same plot is repeated using a decibel vertical scale in Fig. 7.3b (clipped at

dB). We see that the sidelobes are really quite high from an audio perspective. Sinusoids with frequencies near

, for example, are only attenuated approximately

dB in the DFT output

.

We see that

is sensitive to all frequencies between dc and the sampling rate except the other DFT-sinusoid frequencies

for

. This is sometimes called spectral leakageor cross-talk in the spectrum analysis. Again, there is no error when the signal being analyzed is truly periodic and we can choose

to be exactly a period, or some multiple of a period. Normally, however, this cannot be easily arranged, and spectral leakage can really become a problem.

Note that spectral leakage is not reduced by increasing

. It can be thought of as being caused by abruptly truncating a sinusoid at the beginning and/or end of the

-sample time window. Only the DFT sinusoids are not cut off at the window boundaries. All other frequencies will suffer some truncation distortion, and the spectral content of the abrupt cut-off or turn-on transient can be viewed as the source of the sidelobes. Remember that, as far as the DFT is concerned, the input signal

is the same as its periodic extension. If we repeat

samples of a sinusoid at frequency

, there will be a ''glitch'' every

samples since the signal is not periodic in

samples. This glitch can be considered a source of new energy over the entire spectrum.

To reduce spectral leakage (cross-talk from far-away frequencies), we typically use a window function, such as a ''raised cosine'' window, to taper the data record gracefully to zero at both endpoints of the window. As a result of the smooth tapering, the main lobe widens and the sidelobes decrease in the DFT response. Using no window is better viewed as using a rectangular window of length

, unless the signal is exactly periodic in

samples. These topics are considered further in Music 420 and in the ''Examples using the DFT'' chapter.

Since the

th spectral sample

is properly regarded as primarily a measure of spectral amplitude over the range

to

, this range is sometimes called a frequency bin (as in a ''storage bin'' for spectral energy). The frequency index

is called the bin number, and

can be regarded as the total energy in the

th bin (see Parseval's Theorem in the ''Fourier Theorems'' chapter). Similar remarks apply to samples of any continuous bandlimited function; however, the term ''bin'' is only used in the frequency domain, even though it could be assigned exactly the same meaning mathematically in the time domain.