NOTE: THIS DOCUMENT IS OBSOLETE, PLEASE CHECK THE NEW VERSION: "Mathematics of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), with Audio Applications --- Second Edition", by Julius O. Smith III, W3K Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9745607-4-8. - Copyright © 2017-09-28 by Julius O. Smith III - Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA), Stanford University

<< Previous page TOC INDEX Next page >>

The Analytic Signal and Hilbert Transform Filters

A signal which has no negative-frequency components is called ananalytic signal.5.6 Therefore, in continuous time, every analytic signal

can be represented as

whereis the complex coefficient (setting the amplitude and phase) of the positive-freqency complex sinusoid

atfrequency

.

Any sinusoid

in real life may be converted to a positive-frequency complex sinusoid

by simply generating a phase-quadrature component

to serve as the ''imaginary part'':

The phase-quadrature component can be generated from the in-phase componentby a simple quarter-cycle time shift.5.7For more complicated signals which are expressible as a sum of many sinusoids, a filter can be constructed which shifts each sinusoidal component by a quarter cycle. This is called a Hilbert transform filter. Let

denote the output at time

of theHilbert-transform filter applied to the signal

. Ideally, this filter has magnitude

at all frequencies and introduces a phase shift of

at each positive frequency and

at each negative frequency. When a real signal

and its Hilbert transform

are used to form a new complex signal

, the signal

is the (complex) analytic signal corresponding to the real signal

. In other words, for any real signal

, the corresponding analytic signal

has the property that all ''negative frequencies'' of

have been ''filtered out.''

To see how this works, recall that these phase shifts can be impressed on a complex sinusoid by multiplying it by

. Consider the positive and negative frequency components at the particular frequency

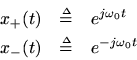

:

Now let's apply adegrees phase shift to the positive-frequency component, and a

degrees phase shift to the negative-frequency component:

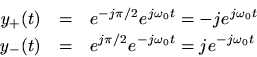

Adding them together gives

and sure enough, the negative frequency component is filtered out. (There is also a gain of 2 at positive frequencies which we can remove by defining the Hilbert transform filter to have magnitude 1/2 at all frequencies.)For a concrete example, let's start with the real sinusoid

Applying the ideal phase shifts, the Hilbert transform is

The analytic signal is then

by Euler's identity. Thus, in the sum, the negative-frequency components of

and

cancel out in the sum, leaving only the positive-frequency component. This happens for any real signal

, not just for sinusoids as in our example.

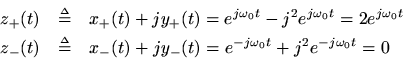

Figure 5.8:Creation of the analytic signal from the real sinusoid

and the derived phase-quadrature sinusoid

, viewed in the frequency domain. a) Spectrum of

. b) Spectrum of

. c) Spectrum of

. d) Spectrum of

.

Figure 5.8 illustrates what is going on in the frequency domain. While we haven't ''had'' Fourier analysis yet, it should come as no surprise that the spectrum of a complex sinusoid

will consist of a single ''spike'' at the frequency

and zero at all other frequencies. (Just follow things intuitively for now, and revisit Fig. 5.8 after we've developed the Fourier theorems.) From the identity

, we see that the spectrum contains unit-amplitude ''spikes'' at

and

. Similarly, the identity

says that we have an amplitude

spike at

and an amplitude

spike at

. Multiplying

by

results in

which is a unit-amplitude ''up spike'' at

and a unit ''down spike'' at

. Finally, adding together the first and third plots, corresponding to

, we see that the two up-spikesadd in phase to give an amplitude 2 up-spike (which is

), and the negative-frequency up-spike in the cosine iscanceled by the down-spike in

times sine at frequency

. This sequence of operations illustrates how the negative-frequency component

gets filtered outby the addition of

and

.

As a final example (and application), let

, where

is a slowly varying amplitude envelope (slow compared with

). This is an example of amplitude modulation applied to a sinusoid at ''carrier frequency''

(which is where you tune your AM radio). The Hilbert transform is almost exactly

5.8, and the analytic signal is

. Note that AM demodulation5.9 is now nothing more than the absolute value. I.e.,

. Due to this simplicity, Hilbert transforms are sometimes used in makingamplitude envelope followers for narrowband signals (i.e., signals with all energy centered about a single ''carrier'' frequency). AM demodulation is one application of a narrowband envelope follower.