NOTE: THIS DOCUMENT IS OBSOLETE, PLEASE CHECK THE NEW VERSION: "Mathematics of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), with Audio Applications --- Second Edition", by Julius O. Smith III, W3K Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9745607-4-8. - Copyright © 2017-09-28 by Julius O. Smith III - Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA), Stanford University

<< Previous page TOC INDEX Next page >>

Complex Roots

As a simple example, let

,

, and

, i.e.,

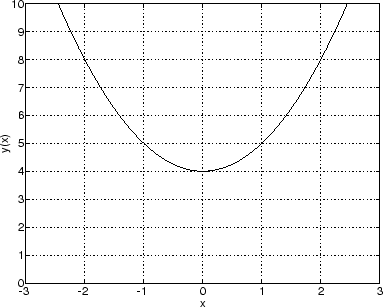

As shown in Fig. 2.1, this is a parabola centered at(where

) and reaching upward to positive infinity, never going below

. It has no zeros. On the other hand, the quadratic formula says that the ''roots'' are given formally by

. The square root of any negative number

can be expressed as

, so the only new algebraic object is

. Let's give it a name:

Then, formally, the roots of ofare

, and we can formally express the polynomial in terms of its roots as

We can think of these as ''imaginary roots'' in the sense that square roots of negative numbers don't really exist, or we can extend the concept of ''roots'' to allow for complex numbers, that is, numbers of the form

whereand

are real numbers, and

.

It can be checked that all algebraic operations for real numbers2.2 apply equally well to complex numers. Both real numbers and complex numbers are examples of a mathematical field. Fields areclosed with respect to multiplication and addition, and all the rules of algebra we use in manipulating polynomials with real coefficients (and roots) carry over unchanged to polynomials with complex coefficients and roots. In fact, the rules of algebra become simpler for complex numbers because, as discussed in the next section, we can always factor polynomials completely over the field of complex numbers while we cannot do this over the reals (as we saw in the example

).