NOTE: THIS DOCUMENT IS OBSOLETE, PLEASE CHECK THE NEW VERSION: "Mathematics of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), with Audio Applications --- Second Edition", by Julius O. Smith III, W3K Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9745607-4-8. - Copyright © 2017-09-28 by Julius O. Smith III - Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA), Stanford University

<< Previous page TOC INDEX Next page >>

General Conditions

This section summarizes and extends the above derivations in a somewhat formal manner (following portions of chapter 4 of

).

Definition: A set of vectors is said to form a vector space if given any two membersand

from the set, the vectors

and

are also in the set, where

is any scalar.

Vectors defined as a list of

complex numbers

, using elementwise addition and multiplication by complex scalars

, form a vector space. Similarly, real vectors

and real scalars

form a vector space.

Theorem: The set of all linear combinations of any set of vectors fromor

forms a vector space.

Proof: Let the original set of vectors be denoted

, where

can be any integer greater than zero. Then any member

of the vector space is by definition a linear combination of them:

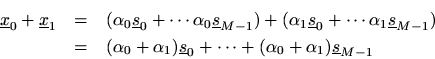

From this we see thatis also a linear combination of the original vectors, and hence is in the vector space. Also, given any second vector from the space

, the sum is

which is just another linear combination of the original vectors, and hence is in the vector space. It is clear here how the closure of vector addition and scalar multiplication are ''inherited'' from the closure of real or complex numbers under addition and multiplication.

Definition: If a vector space consists of the set of all linear combinations of a finite set of vectors, then those vectors are said to span the space.

Example: The coordinate vectors inspan

since every vector

can be expressed as a linear combination of the coordinate vectors as

where, and

,

,

, and so on up to

.

Theorem: (i) Ifspan a vector space, and if one of them, say

, is linearly dependent on the others, then the vector space is spanned by the set obtained by omitting

from the original set. (ii) If

span a vector space, we can always select from these a linearly independent set that spans the same space.

Proof: Any

in the space can be represented as a linear combination of the vectors

. By expressing

as a linear combination of the other vectors in the set, the linear combination for

becomes a linear combination of vectors other than

. Thus,

can be eliminated from the set, proving (i). To prove (ii), we can define a procedure for forming the require subset of the original vectors: First, assign

to the set. Next, check to see if

and

are linearly dependent. If so (i.e.,

is a scalar times

), then discard

; otherwise assign it also to the new set. Next, check to see if

is linearly dependent on the vectors in the new set. If it is (i.e.,

is some linear combination of

and

) then discard it; otherwise assign it also to the new set. When this procedure terminates after processing

, the new set will contain only linearly independent vectors which span the original space.

Definition: A set of linearly independent vectors which spans a vector space is called a basis for that vector space.

Definition: The set of coordinate vectors inis called the natural basis for

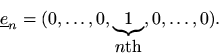

, where the

th basis vectoris

Theorem: The linear combination expressing a vector in terms of basis vectors for a vector space is unique.Proof: Suppose a vector

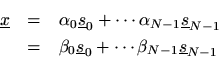

can be expressed in two different ways as a linear combination of basis vectors

:

wherefor at least one value of

. Subtracting the two representations gives

Since the vectors are linearly independent, it is not possible to cancel the nonzero vectorusing some linear combination of the other vectors in the sum. Hence,

for all

.

Note that while the linear combination relative to a particular basis is unique, the choice of basis vectors is not. For example, given any basis set in

, a new basis can be formed by rotating all vectors in

by the same angle. In this way, an infinite number of basis sets can be generated.

As we will soon show, the DFT can be viewed as a change of coordinates from coordinates relative to the natural basis in

,

, to coordinates relative to the sinusoidal basis for

,

, where

. The sinusoidal basis set for

consists of length

sampled complex sinusoids at frequencies

. Any scaling of these vectors in

by complex scale factors could also be chosen as the sinusoidal basis (i.e., any nonzero amplitude and any phase will do). However, for simplicity, we will only use unit-amplitude, zero-phase complex sinusoids as the Fourier ''frequency-domain'' basis set. To summarize this paragraph, the time-domain samples of a signal are its coordinates relative to the natural basis for

, while its spectral coefficients are the coordinates of the signal relative to the sinusoidal basis for

.

Theorem: Any two bases of a vector space contain the same number of vectors.Proof: Left as an exercise (or see [3]).

Definition: The number of vectors in a basis for a particular space is called the dimension of the space. If the dimension is, the space is said to be an

dimensional space, or

-space.

In this course, we will only consider finite-dimensional vector spaces in any detail. However, the discrete-time Fourier transform (DTFT) and Fourier transform both require infinite-dimensional basis sets, because there is an infinite number of points in both the time and frequency domains.

Theorem: The projections of any vectoronto any orthogonal basis set for

can be summed to reconstruct

exactly.

Proof: Let

denote any orthogonal basis set for

. Then since

is in the space spanned by these vectors, we have

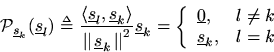

for some (unique) scalars. The projection of

onto

is equal to

(using the linearity of the projection operator which follows from linearity of the inner product in its first argument). Since the basis vectors are orthogonal, the projection ofonto

is zero for

:

We therefore obtain

Therefore, the sum of projections onto the vectorsis just the linear combination of the

which forms

.