NOTE: THIS DOCUMENT IS OBSOLETE, PLEASE CHECK THE NEW VERSION: "Mathematics of the Discrete Fourier Transform (DFT), with Audio Applications --- Second Edition", by Julius O. Smith III, W3K Publishing, 2007, ISBN 978-0-9745607-4-8. - Copyright © 2017-09-28 by Julius O. Smith III - Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics (CCRMA), Stanford University

<< Previous page TOC INDEX Next page >>

Other Norms

Since our main norm is the square root of a sum of squares, we are using what is called an

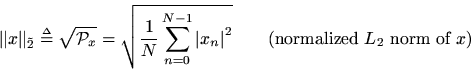

norm and we may write

to emphasize this fact.

We could equally well have chosen a normalized

norm:

which is simply the ''RMS level'' of.

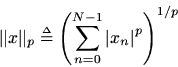

More generally, the

norm of

is defined

The most interestingnorms are

Note that the case

: The

, ''absolute value,'' or ''city block'' norm.

: The

, ''Euclidean,'' ''root energy,'' or ''least squares'' norm.

: The

, ''Chebyshev,'' ''supremum,'' ''minimax,'' or ''uniform'' norm.

is a limiting case which becomes

There are many other possible choices of norm. To qualify as a norm on

, a real-valued signal function

must satisfy the following three properties:

The first property, ''positivity,'' says only the zero vector has norm zero. The second property is ''subadditivity'' and is sometimes called the ''triangle inequality'' for reasons which can be seen by studying Fig. 6.3. The third property says the norm is ''absolutely homogeneous'' with respect to scalar multiplication (which can be complex, in which case the phase of the scalar has no effect).

,

Mathematically, what we are working with so far is called a Banach space which a normed linear vector space. To summarize, we defined our vectors as any list of

real or complex numbers which we interpret as coordinates in the

-dimensional vector space. We also defined vector addition in the obvious way. It turns out we have to also define scalar multiplication, that is, multiplication of a vector by a scalar which we also take to be an element of the field of real or complex numbers. This is also done in the obvious way which is to multiply each coordinate of the vector by the scalar. To have a linear vector space, it must be closed under vector addition and scalar multiplication. That means given any two vectors

and

from the vector space, and given any two scalars

and

from the field of scalars, then any linear combination

must also be in the space. Since we have used the field of complex numbers

(or real numbers

) to define both our scalars and our vector components, we have the necessary closure properties so that any linear combination of vectors from

lies in

. Finally, the definition of a norm (any norm) elevates a vector space to a Banach space.